Destination: The Americas

Brazil

Entre Rios | Sao Paulo | Immigration

Memory, resentment and the politization of trauma: narratives of World War II (Danube Swabians, Entre Rios, Guarapuava - Paraná) by Méri Frotscher, Marcos Nestor and Beatriz Anselmo Olinto, Oct 24, 2014

Construction of "victims' narratives"

Katharina Hech is one of the people interviewed in 1984 whose memories were edited and published in the newspaper. She was born in January 1927 in Setschan (Banat, former Yugoslavia), a town where most of the inhabitants were of German ethnic origin. Katharina was the eldest daughter of a family of Catholic farmers. She had attended agricultural school and helped her family with the work in the fields. In her leisure time, she attended the Schwäbisches Kulturbund, the cultural league of the Swabians. After the invasion of Yugoslavia by the German army, her father went on to serve the Waffen-SS "Prinz Eugen" division to fight the Serbian partisans and left the family taking care of the property. From the beginning of October 1944, with the entry of Russians in Setschan, Katharina, then 17 years old, experienced the most brutal and remarkable days of her life. The interview recorded in 1984, after brief biographical data, begins exactly with the description of the

Russians entering the village, as we will discuss later. Until June 1948, Katharina remained separated and had no contact with her family. In Austria, the family members were reunited and they stayed there until early 1952, when they emigrated to Entre Rios.

The interview by Katharina, like many others published by the newspaper, was given to Jakob Lichtenberger, also a "Danube Swabian" of the former Yugoslavia, born in 1909 in Neu Pasova, Sirmium. Unlike Katharina, who was 18 years younger and had been deported and subjected to forced labor at 17 in the end of the conflict, Lichtenberger had taken an active role in the war as an officer in the Waffen-SS. Lichtenberger was one of the main leaders of Erneuerungsbewegung ("Renewal Movement") in Yugoslavia, which, according to the historian Thomas Casagrande, tried to awaken a sense of ethnic belonging among the Swabians that intended to overlap the horizontal differentiations within the group, replacing them with a vertical delineation of the ethnic group in comparison to others.38 The members of the "Renewal Movement" were ideologically oriented by National Socialism and, with the support of the German National Socialist government, took the lead of the Schwäbisches Kulturbund, the Cultural League of the Swabians in 1939, turning it into a mass organization.

In the late 1930s, Lichtenberger had led the organization of German-origin populations in "self-defense units" (Selbstschutz-Einheit), called Mannschaften, which received weapons from the German government. Those units would later, after the occupation of Yugoslavia by Germany in 1941, form the core of Bürgerwehr to fight the partisans. 39 Lichtenberger and another activist of the movement were recommended by Sepp Janko to the German government to be the leaders of the Waffen-SS, with Lichtenberger, therefore, being sent to Germany for training.40 During the war, he fought on the Balkans and the eastern front. After that, he fled to Germany fearing that we would be arrested and turned over to the U.S. occupation forces in Austria.41 After retiring as a teacher in Germany, Lichtenberger came to Entre Rios in 1974.42

At the time of the interview, Lichtenberger was a schoolteacher and a recognized authority in the countryside of Entre Rios. Between 1984 and 1985, he conducted interviews, speaking in dialect, with locals who had witnessed the war as adults, representing them in the brief headings of the transcripts as "accounts". The goal that was implicit in the form and content of the interviews was to create narratives of war victims. The interviews were transcribed and typed without the intervention of the interviewer and delivered to the local museum for safekeeping and preservation.

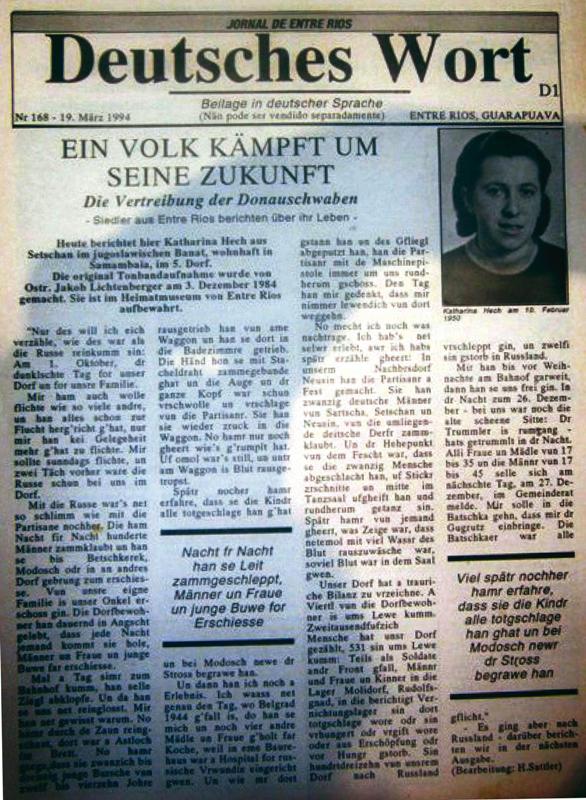

Only 10 years later, in March 1994, excerpts from the "account" of Katharina were published in two issues of Jornal de Entre Rios, in the series mentioned before.

In the first edition, the passages refer to the arrival of the enemies and the shootings of Germans that occurred in Setschan (Figure 2). In the second one, the passages refer to her deportation to Ukraine and the forced labor to which she and other Swabians were subjected. Besides the fact that she was a witness to the events that took place during the arrival of the partisans and Russians, being one of the deported women made Katharina an ideal and authorized voice to compose a tragic narrative of that people. Even today, Katharina's name is suggested by other residents of the colony for a testimony about the past of war.

Figure 2 The transformation of the interview in a testimony: the publication of the interview with Katharina Hech. Source: Deutsches Wort (supplement of the newspaper Jornal de Entre Rios), Entre Rios - Guarapuava, n. 168, 19.03.1994, D1.

The transcript of the interview originally given, on which the editions were based, has 28 typewritten pages.43 In them, the questions and interventions of the interviewer are suppressed or, in several passages, embedded to the own speech of the interviewee by the transcriber.44 Thus, the dialogical process of producing the interview was erased by the transcript, which mischaracterized the interview, transforming it into a testimonial "account".

The passages quoted in both editions of the newspaper add up to only three pages, which required a considerable selection of excerpts, indicated at the end of the published "account" by the word Bearbeitung (editing), followed by the name of the publisher. The cuts are not indicated in the edited text, which, however, has fluidity and consistency for the purposes of the series.

The events addressed in the editions are the most extreme and brutal that Katharina experienced directly or indirectly. Death, humiliation, fear, separation from the family, hunger, cold, and uncertainty about the future are some of the recurring themes. As the transcription of the original "account" advances, fewer fragments were selected to compose the published text. Much of the most brutal events and facts considered relevant were reported right in the beginning, because it seemed clear to Katharina that her speech should be a testimony about the suffering of the "Danube Swabians".

The part published in the first edition of the paper addresses the short period of three months, from the beginning of October to the end of December in 1944, which comprises the arrival of the Russians until her deportation. At the very beginning of the edited interview, and also of the transcribed interview, Katharina talks about it: "I just want to tell you how it was when the Russians entered [the village]: on the first of October, the darkest day for our village and our family".45 The use of the second person plural pronoun (eich: you) as predicate indicates the awareness of not only talking to the interviewer, but to potential listeners/readers of her testimony.

Although the arrival of the Russians was represented as "the darkest day for our village and our family", a few lines later, Katharina relativizes her position before them: "With the Russians it was not as terrible as then with the partisans".46 In the sequence, she comments on the shootings done by partisans, in one of which her uncle was killed. She herself did not watch this. But she talks about other shooting, adding information that she found out later:

Once, we arrived at the train station [probably previously destroyed by the German troops], and we had to take the cement off bricks. Then they [partisans] did not let us in. We did not know why. We look through the fence, there was a hole in the board and through it we saw that they pushed twenty, even thirty boys, ages 12 to 14 years old, off a wagon toward the bathrooms. They had already tied their hands with barbed wire, and the eyes and the entire heads were already swollen and bruised by the partisans. Then they pushed them again back to the wagon. We still heard a noise. Suddenly everything was silent, and under the wagon blood began to drip. Later, we learned that they had killed those children and buried them in Modosch, on the roadside.47

In the excerpt published shortly afterwards, Katharina talks about the fear she felt of being murdered herself. She and other women had been taken to cook for wounded Russian soldiers in a house used as a makeshift hospital: "And when we were standing there cleaning the slaughtered birds, the guerrilla men kept firing guns around us. On this day we thought we would not get out of there alive". This passage was preceded by the phrase: "And then I have one more experience to tell", signaling, as with other phrases and expressions present in the narrative, that there was a previous reflection on what would be relevant to narrate.

Soon after that, both in the oral and in the published versions, Katharina again emphasizes the will to register (nachtragen) another episode, even though it has not been witnessed by her, as she explains herself:

I want to register something else. It was not I who experienced it, but I have heard it later. In Neusin, our neighboring village, guerrilla men threw a party. They took twenty German men of the villages around Sartscha, Setschan and Neusin. And the highlight of the party was that they massacred those twenty people, cut them into pieces, stacked them in the middle of the hall and danced around them. Later we have heard, from someone who was a witness, that not even with plenty of water it was possible to get the blood off the floor, so much blood there was.48

The iconic story of the macabre dance with parts of the dismembered bodies and the blood-soaked room, and others that she has heard of and narrates during the interview reveal the sharing of memories of traumatic events among the survivors. The sharing, done orally and reproduced also through publications, fulfills a purpose in the building of a collective identity of victims. The trauma pointed out in Elfes' book and in Grossner's report, both mentioned in the beginning of this article, found its treatment on the composing and editing of memories as the ones from Katharina, fragmented and exposed in public space.

Being one of the deported women made Katharina an ideal and authorized voice to compose a tragic narrative of that people

The quoted passage also draws our attention to the mechanism of including extraneous information in the testimony. The traumatic memory absorbs them in the creation of an autobiographical narrative. Although Katharina states that she will tell "how it was when the Russians arrived", she narrates these events not only from her experiences but also from information shared later, or even obtained through the reading of books and other printed materials. Katharina becomes a subject of memory, an authorized speech about the past, not only because of her experiences but also because of what she has found out by other means. Hence also the accuracy of some of the data presented, such as the number of dead people in her village:

Our village has a sad balance to register. A quarter of the population died. Our village had two thousand and fifty people, 531 died. Some fell in the front as soldiers. Men, women and children were murdered in the camps of Molidorf, Rudolfsgnad, in the infamous extermination camps, or were beaten to death, or died of starvation, or were poisoned, or died exhausted from overwork or starvation. One hundred and thirteen people from our village were deported to Russia and twelve died in Russia.49

The narrative of the passage is structured by the listing of the tragic fates of the inhabitants of her village. These are figures that Katharina would hardly kept in mind without the aid of some support material. Like her, many immigrants in Entre Rios have at home a Heimatbuch (Heimat: home/homeland; Buch: book), a book illustrated with photographs of, among other aspects, the history of the place of origin. These books were organized and published after the war by entities of Germans expelled from the same place of origin, as a result of a whole effort to rebuild the German past of those places and relate it to the history of families. It is the lost homeland on paper, which many immigrants keep and show when they speak of their native land.

50 In the three interviews conducted by the authors with Katharina, for instance, in 2005, 2010, and 2012, she showed photos and documents of the Heimatbuch,51 which she kept in her house, in order to illustrate, prove statements, or reinforce arguments in the oral narrative.Giving a testimony appears to be a process, because making an autobiographical narrative of a past event involves different components of credibility for it to be perceived as a testimony. According to Paul Ricoeur, this process involves first a demarcation of the border between fiction and reality, in other words, it is necessary to deal with suspicions.52 Then, the author points out that there is an opacity of the narrative, that is, the interests of the narrator and of the receiver are different, because narrating is always a dialogue; thus, the testimony must face the public confrontation and, in that process, it needs to be constantly reiterated. Only then a narration becomes trustworthy testimony and even a habitus of a community. Katharina's speech seems to be able to successfully accomplish this operation when edited and published by the newspaper.

The end of the first segment of the published "account" refers to the main theme of the next issue: the deportation. Katharina and others who were chosen for deportation had initially been informed by partisans that they should help harvest the corn plantations in the Batschka region, whose residents had fled before the arrival of the Russians. But, in fact, as the editor announces, everyone would be deported to "Russia". When he clarifies that "[...] we will report on this in the next issue [emphasis added]",53 the editor also implies the role of the newspaper in the composition of that "account".

NEXT: "The thick brown crust": resentment and forgetting in survival

Footnotes

38The historian Thomas Casagrande highlights the abuses of ethnicity committed by the leaders of the "Renewal Movement", whose measures resembled in many aspects the National Socialist policy in the Third Reich. Its program and measures seek to arouse a feeling of ethnic belonging, which should overlap the horizontal differentiations within the group, replacing them with a vertical delineation of the ethnic group in relation to others. Thomas Casagrande, Die Volksdeutschen SS-Division "Prinz Eugen": Die Banater Schwaben und die Nationalsozialistischen Kriegsverbrechen, Frankfurt am Main, Campus Verlag, 2003, p. 137.

39Thomas Casagrande, Die Volksdeutschen SS-Division "Prinz Eugen": Die Banater Schwaben und die Nationalsozialistischen Kriegsverbrechen, Frankfurt am Main, Campus Verlag, 2003, p. 156-157.

40Thomas Casagrande, Die Volksdeutschen SS-Division "Prinz Eugen": Die Banater Schwaben und die Nationalsozialistischen Kriegsverbrechen, Frankfurt am Main, Campus Verlag, 2003, p. 143.

42"Nachruf", Revista de Entre Rios, Guarapuava, março de 2005, p. 7. In this obituary published in the local newspaper, Lichtenberger's biography is described with positive adjectives.

43Interview with Katharina Hech, conducted by Jakob Lichtenberger. Entre Rios, colony of Samambaia, Dezember 3rd, 1984. The recorded tape and the transcription belong to the archive of the historic museum of Entre Rios.

45"Ein Volk kämpft um seine Zukunft. Die Vertreibung der Donauschwaben. Siedler aus Entre Rios berichten über ihr Leben", Deutsches Wort (Suplemento do Jornal de Entre Rios), Entre Rios - Guarapuava, 19 de março de 1994, D1.

46"Ein Volk kämpft um seine Zukunft. Die Vertreibung der Donauschwaben. Siedler aus Entre Rios berichten über ihr Leben", Deutsches Wort (Suplemento do Jornal de Entre Rios), Entre Rios - Guarapuava, 19 de março de 1994, D1.

49"Ein Volk kämpft um seine Zukunft. Die Vertreibung der Donauschwaben. Siedler aus Entre Rios berichten über ihr Leben", Deutsches Wort (Suplemento do Jornal de Entre Rios), Entre Rios - Guarapuava, 19 de março de 1994, D1.

50The communicative nature of memory is evident in many of the interviews with immigrants and descendants in the colony through the developed project. Many of them receive the researchers already with photographs, documents, and books arranged on the table, including in their narratives information and interpretations that are in these sources or even building their narratives from them.

52Paul Ricoeur, A memória, a história e o esquecimento, Campinas, Editora da Unicamp, 2007, p.172-175.

53"Ein Volk kämpft um seine Zukunft. Die Vertreibung der Donauschwaben. Siedler aus Entre Rios berichten über ihr Leben", Deutsches Wort (Suplemento do Jornal de Entre Rios), Entre Rios - Guarapuava, 19 de março de 1994, D1.

DVHH < Destination: The Americas < Brazil < Entre Rios < Memory, resentment and the politization of trauma: narratives of World War II (Danube Swabians, Entre Rios, Guarapuava - Paraná) < Construction of "victims' narratives"