|

Villages

Lorrains En

Roumanie |

|

by André Rosambert

Written in the French magazine publication: L'Illustration*,

01 April 1933 -

Issue N. 4700

Translated by

Nick Tullius;

Contributed & Published @

DVHH by

Jody McKim Pharr

- 12 Oct 2010

|

|

|

| |

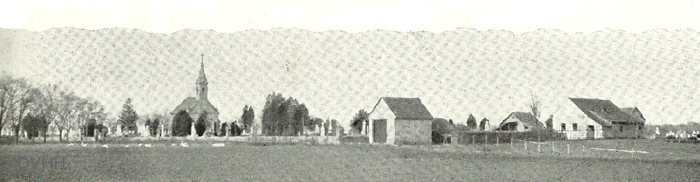

The church of Saint-Hubert, where until 1840 the sermon was delivered in

French every third Sunday of the month; on the right, the parish house |

|

LORRAINE VILLAGES IN ROMANIA |

|

|

The peace

treaties

integrated

into our

friend and

ally

Yugoslavia

three

villages

with a

population

that almost

completely

has its

origins in

Lorraine.

|

|

|

Border between the villages of Charleville & Seultour |

Situated at

an equal

distance

from the

Hungarian

city of

Szeged and

the Romanian

city of

Timisoara,

on the line

that once

led from

Budapest to

Bazias, the

small towns

of

Saint-Hubert,

Charleville

and Seultour

proudly

carry the

epithet

“Welsch

villages”,

given to

them by

their

neighbours,

the villages

called

“Swabian”,

whose

inhabitants

once

emigrated

from

Germany.

The Middle East has certainly accustomed us to these curious colonisations;

but the

existence of

“French”

agglomerations

along the

Romanian-Yugoslavian

border,

isn’t that

something

unexpected,

and that

among the

newcomers to

the

hospitable

home of the

great

Yugoslavia

we count

brothers of

our race,

isn’t that a

unique turn

of events?

How is it that the travellers that visited this region since Hungarian

times, where

France had

industrial

as well as

financial

interests,

passed quite

close by

these

villages,

without

paying them

the

slightest

attention?1

And how is

it that

since the

armistice,

the detailed

reports from

Yugoslavia,

like those

from

Romania, did

not even

give a hint

about the

existence of

these

distant

compatriots?

For this

abandonment

and

disregard,

regrettable

as they are,

there is an

explanation:

the |

|

Lorraine

villages of

Yugoslavia

are actually

not very

easy to

find, and

when one

finds them,

one must

have studied

them to

understand

their

profound

originality.

Grouped in a triangle at the extreme north-east of the Kingdom of

Yugoslavia,

in a lost

corner of

the Danube

Banat, at 4

kilometres

from Romania

and 50

kilometres

from

Hungary, the

three towns

of

Saint-Hubert,

Charleville

and

Seultour,

even though

they are

located on a

great

railway

line, are

only served

by a little

steam

tramway that

connects the

station of

Sveti Hubert

to the city

of Velika

Kikinda.

And once one enters Saint-Hubert, the most important of the three “sister

communities”

because it

counts 1500

souls,

whereas

Charleville

has 800 and

Seultour

950, one

does not

notice

immediately

a great

difference

between

these

Lorrain

villages and

their

neighbouring

villages,

like Nakovo

or Heufeld,

the

population

of which is

mostly of

German

origin.

That is, for two generations, the descendants of our compatriots, either

from

|

|

|

The three Lorraine villages in the Yugoslavian Banat |

France or

from

then-independent

Lorraine,

immigrated

to the Banat

between 1750

and 1790, no

longer speak

French;

German

became their

usual

language,

and no one

can blame

them.

Attracted to this fertile country by empress Maria-Theresia, whose possessions in

Southern

Germany

(Baden and

Würtemberg)

facilitated

her

recruitment

among the

populations

of Lorraine

and Alsace,

the first

French-speaking

colonists

arrived in

the Banat

with

families

from Germany

and

Luxemburg,

all destined

to

repopulate

the

territories |

|

between

Tisa, Temes

and Danube,

that had

been

devastated

by the

Turks.

Saint-Hubert,

Charleville

and Seultour

were founded

in 1771 by

two hundred

nine

families,

nine out of

ten of which

were

French-speaking.

But on December 6, 1774, an imperial edict imposed the teaching of German

to children

in schools,

and the

systematic

Germanisation

of all

non-German

colonists

(Frenchmen,

Italians,

and

Spaniards)

was a great

preoccupation

of Emperor

Joseph II.

It is in church that French usage was maintained the longest, because the emigrants had

brought

along

missals; the

teaching of

catechism

was in

French for

many more

years and

the sermon

was

delivered in

French every

third Sunday

of the month

until 1840.

The sermon

was

delivered in

French at

the church

in

Saint-Hubert,

for all

three

villages

together, by

priests or

religious

personnel

brought in

from

Temesvar,

headquarters

of the

diocese.

The last inhabitant who spoke French fluently was a farmer named Pierre Hanrio,

who

originated

in Fonteny,

arrived in

Seultour as

a little

child with

the first

colonists,

and died in

1866, nearly

one hundred

years old.

In 1902 when Raymond Recouly, then a young associate, visited the Lorrain

villages of

the Banat

during an

investigation

of

nationalities

and races in

Austro-Hungary,

he still

found an old

woman who

told him

that in her

childhood

she had read

the gospel

in French.

Alas, the Hesse, the Mourgeon, the Hamant, the Colin, the Perrin, the Grosdidier, the

Mathieu, the

Leblanc, the

Georges, had

become Hess,

Muschong,

Hamang,

Kolleng,

Perreng,

Groditje,

Matje,

Leblang,

Schorsch,

did not know

the

sweet

language of

France,

other than a

few rare

expressions.

But it is

wrong and it

would be

unjust to

say, as I

have read in

certain

hasty

reports,

that the

descendants

of our

compatriots

are today

“Germanized”

and have

become

“Swabians.” |

|

A house with

covered

corridor in

Charleville

(1) With

the

exception of

Dr. Louis

Hecht, who

in 1878,

made an

inquiry into

the Alsacian

colonies in

Hungary (Mémoires

de

l’Académie

de Stanislas,

1878. Nancy,

Berger-Levrault,

1879).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A wedding

procession

arriving at

town hall

|

|

|

black eyes

Joseph II commented at

his first trip to the

Banat, made the

inhabitants of the

“sister-villages” so

sympathetic to their

“Swabian” neighbours,

with whom they readily

allied themselves.

Great lovers of music,

they have a famous

choir, conducted by Mr.

Leblanc, an old teacher

from Saint-Hubert, as

well as two orchestras.

The one we listened to,

conducted by the skilful

baton of Mr. Stofflet,

had learnt in only two

days the Lorraine

march, in honour of

their French guest. The

teacher from Seultour

had performed the feat

|

Not the

fantasies

applied by

imperial

civil

servants to

their family

names, not

the mixed

marriages,

nor the

total

abandonment

in which

they were

left until

recently by

their

country of

origin, made

them loose

the memory

of their

ancestral

land.

Is it known that in 1930, the initiative of a farmer whose origins are in

Marsal and

Saraltroff,

author of a

Chronique

of the three

sister

villages,

lead to the

founding in

Saint-Hubert

of a little

Lorrain

museum,

intended to

become the

conservatory

of ancestral

traditions?

Temporarily installed in an agricultural cooperative, a little yellow

building,

with a huge

roof

descending

very low,

very similar

to the

houses of

the village,

the Lorraine

museum of

Saint-Hubert,

whose

founders

gave it the

suggestive

name

“Country

museum”,

comprises a

tiny

antechamber,

a single

room, and a

hangar.

The hangar houses a cart and a plough from the time of emigration.

In the antechamber, on an ancient table with pretty lathe-work legs, Mr.

Nicolas Hess,

founder and

caretaker of

the museum,

placed the

old wooden

measuring

devices once

used in the

village

mills.

Finally, the “main room” of the museum, a little room with earthen floor an

whitewashed

walls,

houses the

treasures

that were

until now

lovingly

preserved in

the

families,

but which

the untiring

dedication

of Mr.

Nicolas Hess

made them

give up, for

the benefit

of the

common good:

clock,

dresser,

chest-dresser,

cabinet with

panels

prettily

decorated

with

flowers, bed

and cradle

naively

painted,

spinning

wheels, an

old butter

churn,

halberd and

lantern of

the night

watchman,

and the

silver-tipped

sticks of

the mayors

of the three

villages, an

Alsatian

waistcoat

with silver

buttons,

etc.

The cabinet

is filled

with

documents,

among which

there are

birth

certificates

issued in |

|

Parroy,

in

Bertrambois,

and a

venerable

French

missal.

In a tray, a Lorraine flag that resembles those that the people of Nancy

and Metz

placed in

their

windows and

which

according to

an order by

king

Alexander

allows the

little

museum, now

a public

museum, to

fly next to

the

tricolour of

our Yugoslav

allies.

|

|

|

The village mill, which dates back to the early time of the colonization |

A gesture by

Mr.

Albert

Lebrun,

whose

goodwill

deeply moved

our friends

from

Saint-Hubert

to have in

their own

museum the

portrait of

the first

magistrate

of the

French

Republic,

wearing his

signature,

alongside

that of

another

great

Lorrainer:

Marshal

Lyautey.

The Lorrainers of Yugoslavia, even though they lost the use of their

ancestral

language,

preserved

many customs

of the

country:

first name

Nicholas

given to

almost all

first-borns;

distribution

of sweets

during

baptisms;

plantation

of the

"May-tree";

rattle on

Good Friday;

use of an

“offering”

at weddings

and

funerals,

some kitchen

recipes,

pies and

Lorraine

flat-cakes;

use of an

old card

game still

called "la

préférence":

all customs

peculiar to

the "Welsch"

Banat

villages and

that one

would seek

in vain in

the

"Swabian"

Villages.

[Translator’s

note:

Contrary to

the author’s

affirmation,

several of

these

customs were

common in

the Swabian

villages of

the Banat].

The

descendants

of our

compatriots

kept to this

day that

virtue of

frugality,

of which the

Lorrainers

were so

justifiably

proud. Their

simple and

natural

joyfulness,

the beauty

of their

women, on

whose

beautiful |

|

of composing

an

orchestral

score from

the text for

piano and

violin that

he had

available.

Music played an important part in all great events. It played its part at

funerals,

the

musicians

marching in

pairs, along

the houses,

with the

rest of the

procession,

while the

hearse

advanced

alone in the

middle of

the 50 to 80

meters wide

streets.

And, during

marriages,

the music

followed the

row of

invited

guests that

moved like a

procession

to the house

of the bride

and groom,

to conduct

them to the

town hall,

then to

church…

Then, after

the dance

that lasted

until dawn,

the young

couple is

conducted to

their home;

it's a last

serenade

which gives

the signal

that the

celebration

is over.

And that is how three thousand descendants of Lorrainers lived, 1400

kilometers

away from

Lorraine.

Their

ancestors

had run away

from the

oppressive

administration

of Mr. de

La

Galaizière:

they had the

good fortune

of finding

in the Banat

a fertile

soil, and

there are no

longer any

poor people

among them.

But their

fate was

even more

favourable

than they

had dared to

hope: their

home is now

incorporated

in the noble

and proud

Yugoslavia,

|

|

|

Graves of Lorraine emigrants

to the Banat |

and it is

under the

banner that

has the same

colours as

ours, good

and loyal

citizens of

a country

dear to all

Frenchmen,

they engage

with joy in

their

peaceful

work in the

fields.

ANDRÉ

ROSAMBERT

(Written in French in

1934)

~ Translated

by Nick

Tullius 2010

|

|

|

|

The three

Lorraine

villages in

the

Yugoslavian

Banat

[Translated by

Nick Tullius;

Contributed & Published @

DVHH,

Jody McKim Pharr

- 12 Oct 2010]

[Article discovered & contributed by Jody McKim and translated from French to English

by Nick Tullius & Published @ DVHH - 09 Sep 2010 by Jody McKim Pharr.]

L'Illustration

was a weekly French

newspaper published in

Paris. It was founded

by Edouard Charton; the

first issue was

published on March 4,

1843.

In 1891,

L'Illustration

became the first French

newspaper to publish a

photograph, and in 1907,

the first to publish a

color photograph. It

also published Gaston

Leroux' novel Le mystère

de la chambre jaune as a

serial a year before its

1908 release.

During the Second World

War, L'Illustration

was published by Jacques

de Lesdain, a

collaborator; after the

Liberation of Paris, the

newspaper was shut down.

It re-opened in 1945 as

France-Illustration, but

went bankrupt in 1957.

|

|

|

|