|

The Deportation to the Baragan – 50 years on

Translated from the Lenauheimer

Heimatblatt 2001 by Diana Lambing

The war

was over and a new beginning was now to

be made. At first, people still owned up

to 50 hectares of land which they

farmed, but gradually Communism took

over the monopoly and the economy

declined year by year. The produce had

to be handed over to the State at below

the manufacturer's price so that it

wasn't worth doing anything any longer.

Three years later, nobody had more than

five hectares of farmland left, which

they received as frontline soldiers and

which had to suffice for them to live

on. This meant the livestock had to be

reduced to one horse, one cow, a couple

of pigs and a few chickens for their own

use. When the LKW (the agricultural

collective) was established in 1949,

they needed the large-scale buildings

and so the owners had to move into other

houses. Nearly everyone had a job on the

side as well, in order to just get by.

Life became aimless.

And so, as the years

went by, the Communist regime slowly

gained control of everything. The

powerful Soviet Union was their role

model. All confiscation of assets and

businesses was copied from them. People

were easier to handle when they owned

nothing. They were more dependent and

submissive. The State was the absolute

ruler of the whole population.

From 1950 onwards,

the situation between the Soviet Union

under Stalin, and Yugoslavia under Tito,

worsened. There were ideological

differences between the two. Tito didn't

want to be as subservient as the

powerful Stalin would have liked. This

was the reason for moving those

untrustworthy people not faithful to the

regime who lived in the zone bordering

Yugoslavia. Big Brother, the Soviet

Union, had already demonstrated this

many times. On the other hand, there

were still areas in south-eastern

Romania which were sparsely populated

and where the State needed cheap labour

for the newly-founded agricultural

collective. So one day the decision made

by the government to deport a section of

the population from this border zone to

the so-called Baragan Steppes was

carried out.

The Baragan Steppes

are situated in the south-eastern part

of Romania, an area of about 60

kilometres (40 miles) wide along the

Danube which now flowed from South to

North. It is a wide, treeless plain but

with fertile soil, and which is very

sparsely populated. It has something of

the endlessness of the Prarie and of the

romance of the Hungarian Puzta, but

above all, of Siberia's cruelty. It is

bleak and strange. Motionless, yet with

a constant wind passing through,

sometimes caressing, sometimes raging.

The winters here are very harsh and

cold, with predominantly bitterly cold

winds from the North-East. The summers

are relentlessly hot and dry. There had

been a few large private owners who had

worked the soil but they had all been

dispossessed and made to work for the

State. Now, cheap labour was needed.

The people had

already completed their work. The

tilling for the maize and potatoes, and

for the garden, was done. The barley had

been reaped and put into heaps a few

days earlier. But it was still all for

nothing, and only for the others. People

sensed something in the air. Already

several days previously, empty wagons

had been shunted back and forth on the

railway. These couldn't be for the new

harvest already. For the past two weeks,

a military officer (police) had been in

the village and had been snooping

around. He checked several people's

passes for authenticity, but this was

only a diversion. There were also

several soldiers around who took

measurements in the village and at the

edge of the parish. They drew brief

sketches on the map and marked these

points on the ground with small heaps of

earth. The local people had no

explanation for it, even though several

of the heaps stood higher than the

soldiers themselves. Did they know what

they were doing? Hard to believe.

Everything was so secretive that nobody

knew what was coming. The snooping

officer also had an aerial view of the

village with him. The picture was of

such a high resolution that every detail

could be seen on it.

At last the day

arrived when the whole truth came out.

It was Monday, 18th June 1951. Already

on the Sunday evening a whole section of

the Miliz (police) had arrived and

dismounted at Karl Bieber's old house in

Kirchengasse (Church Street), but not to

be billeted or to sleep overnight. Only

later did people find out that a whole

regiment of the 'Securitate' had arrived

in Triebswetter near Lenauheim and that

from there they were split up and sent

into other villages. This was a group

which came under the jurisdiction of the

Home Office and which was responsible

for the internal security of the

country. All those taking part in the

performance were dressed in new uniforms

and knew nothing about what was going

on. They were only told what to do at

the very last minute. Even the train

drivers who managed the transport knew

nothing. The organization of the teams,

who were to carry out the deportation,

was made outside the village on the

Hutweide (meadow). Every policeman was

allocated five soldiers and five

envelopes in which five families were

named. At exactly 5 o'clock, things

began to move. They marched at the

double into the village. These groups

all came through Kirchengasse and looked

for their house numbers. Some of the

folk stood at their windows and watched

as they looked for the house numbers

with their torches. Soldiers asked where

this or that number was. Others ordered

people to close their windows. Finally,

each group was standing by a house

number. They had achieved their first

goal. The policeman knocked on the

window and asked who lived there. Then

he read his little speech from his sheet

of paper, saying that they were to be

moved away from here and telling the

family what they were allowed to take

with them. No weapons, radios or cameras

were allowed. Every family would get a

goods wagon for the transport of

animals, carts, food, furniture and

clothing. They had three hours to pack.

One soldier would stay as a guard.

Nobody was allowed to leave the house.

If anyone needed a means of transport to

get to the station, it was available.

This soldier was responsible for getting

the family as far as the station.

Resistance was pointless.

The people packed

everything they wanted to take with them

and loaded it onto the cart. But it

wasn't easy loading furniture, food and

livestock. It took ages until they were

finished. Finally, they drove to the

station. They camped in the open by the

station until the goods wagons (box

cars) arrived. It looked like the annual

market. Everything got mixed up. When

the train with the wagons arrived,

everything was loaded from the spot

where the people were standing, except

for the livestock. Horses and cattle

were led one after another up the ramp

to the wagons. When the first 30 wagons

had been loaded, the next 30 were

loaded. Only once they were in Hatzfeld

did the 60 wagons form a long train, and

it was only then that people saw who

else was present. Two families were put

into wagons without any large livestock.

There were those who were afraid that

their families would be torn apart and

that they would end up in separate

places.

From Hatzfeld on,

things moved quickly, as the other

transports had all been set to a

timetable. At Temeswar railway station

there was only deportee transport. Only

the staff responsible for this was

allowed on the station. No-one else was

permitted. Relatives of the deportees

who lived in Temeswar visited their

families and friends at the station

wherever possible, using roundabout

ways. We don't know how they managed it,

nor how long they had to wait.

On the second day,

they went onwards from Temeswar. They

travelled South through Oltenien, where

the first transports from other villages

were too, and then, for reasons unknown,

the transport was diverted from Lugosch

via Ilia through Siebenbürgen

(Transylvania). People now realised that

their destination was beyond Bucharest.

The train was accompanied by officers

and soldiers who travelled in a

passenger car. As soon as the train

stopped, soldiers with guns were

positioned all along the train on both

sides. Civilians were not allowed to

speak to the deportees. After two or

three days, the people had already got

to know one another. There was no point

in escaping as they would have been

caught later. The horses were nervous

most of the time and kicked around with

their front hooves. The crates in which

the chickens were housed didn't all hold

out and the chickens flew around the

wagon. Whenever the transport came to a

halt anywhere, officer guards came with

a list and asked everyone where they

wanted to go. They were actually only

doing a check to make sure everyone was

still there. In our fellow-countrymen's

train there were many intelligent

Bessarabian Romanians who said that they

were being deported to Russia. All the

signs looked that way, and the direction

they were moving was right, too.

Finally, after a long journey, the

railway station at Gura-Ialomita came

into view. One station, all alone in the

open landscape, with no village to be

seen far and wide. It was the end of the

railway line and also seemed to be the

end of the world. The line was supposed

to carry on from here across the Danube

to the Black Sea, but it never got that

far during the war, and the line ended

in nothing.

This is where the

people unloaded everything. The men with

the horses and carts full of sacks,

cows, pigs and chickens. Most of the

women travelled on a truck which was

already standing by and which was loaded

with all the other odds and ends. Most

of them had brought along their best

bedroom, kitchen and other belongings

with them. Those who had arrived earlier

at their destination, which was about 12

kilometres (8 miles) away, they said,

had a house plot reserved. What they saw

there wasn't much. So they carried on.

The drivers formed a column and were

escorted to their destination. People

had trouble with their nervous horses.

The carts were heavy, but it wasn't the

load on the cart, but the edgy

restlessness of the horses that was to

blame. They often bumped into each other

and pulled backwards. The cows, which

were tied to the carts, would generally

follow them quietly, but not by this

means of travel. Suddenly, several cows

had torn themselves away from the carts

and run off. The drivers themselves

couldn't leave their carts. They

couldn't always calm the horses down.

People helped each other to catch their

animals which had run away. As the

horses grew tired, they calmed down

again. Gradually, the road came to an

end. It was already dark and one could

already see from afar improvised tents,

just like at the annual markets that

used to be. A star also shone from a

building, as though it was guiding the

people to the future in their new

homeland. After a journey of 12

kilometres, they reached their

destination. After a bit of searching,

the family members found each other

again, together with all their worldly

goods. Nearby were both old and new

neighbours.

As it grew light the

following morning, everyone saw their

own post which had already been stuck

into the ground with their number on it

and which marked the measured-out plot

for their house. It was to be their

future house number. At the moment, it

was just a field of stubble where barley

had once been harvested. First of all,

they needed to orientate themselves in

order to find out where they were. Along

one row at the edge of the future

settlement, they were all villagers from

Lenauheim, the first ones to arrive.

Those who arrived later from Lenauheim

were allocated places far away in

another part. They needed to

provisionally organise themselves. There

was no water here – this was brought in

from the Danube, which was close by.

Each street – if you could call the

piles of household goods that – received

a large barrel of water which had to be

constantly replenished. It tasted of

chlorine, used to keep any anticipated

germs at bay. Everyone searched for, and

believed they would find, a better well,

but all in vain. All the water found in

the ground was salty and undrinkable.

Nothing much could be

done during the day. It was a scorching

tropical heat with no trees or bushes to

give any shade. After a thorough look

around, they found that they were in the

eastern part of the settlement. There

was no mention of any village; nobody

could make out any streets because

everyone had just unloaded their

belongings right where the cart had

stopped. Then everyone went about their

own business. The people from Lenauheim

were in the last row of houses on the

eastern edge of the village, the one

nearest the Danube which was only 500

metres away and from where, for the next

five years, they would get their

drinking water. This water, once it had

been standing and the sediment had

settled, was the best water for

drinking, and the softest for washing.

There are no pathogens or bacteria in

flowing water.

This village had been

measured out in a horseshoe shape by

engineers prior to the arrival of the

deportees. It was situated at the mouth

of the river Ialomita, about 500 metres

from the Danube. There were 738 house

plots and 2,176 deportees as

inhabitants. Many house plots were not

colonised and remained empty.

Immediately ahead to the North was the

State farm with its buildings and

stables. About three kilometres away

from the Danube to the South was the

village of Giurgeni. This was where the

only road was that led to the harbour

town of Constanta on the Black Sea. As

there was no bridge here, one had to

cross the Danube on a ferry. In the

beginning, the new village was named

after the old village, 'Giurgeni-noi'.

Later it was changed to 'Rachitoasa.'

The first shelter

usually consisted of the space between

two cupboards, over which the side parts

of the beds were laid, covered by a

haystack cover and a 'Plache', as

protection from the rain. The whole

thing had to be secured in order that

the wind wouldn't blow it all away.

Horses and cattle were tied to the

carts. Piglets were put into a pit which

was dug out deep enough to prevent them

from jumping out. Most of them were sold

because of a lack of pens to house them

and a lack of pig feed. It would have

been better to fatten them up, but with

what? The chickens stayed in the

upturned crates. They were able to

exercise in the nearby field of lucerne.

Chickens return by instinct in the

evening to sleep where they awoke in the

morning. People weren't worried about

the chickens, as they searched for food

by themselves. There were beetles in the

lucerne. They were very grateful for

this food and hence laid many eggs. The

chickens covered the need for eggs for

many people.

A second

transportation from Lenauheim went to

Dilga, which was situated along the

railway line between Bucharest and

Constanta. A third transport train from

Lenauheim came to Giurgeni-noi. About

ten trains full of deportees were

brought to the 'new village' (Neudorf).

Two trains came from Lenauheim and two

from Triebswetter. There were also

trains from Perjamosch and Gross

Sanktpeter, and from Hatzfeld ten wagons

with Bessarabian Romanians from Otelek,

Pustinisch, Deutsch-Beregsau, Gross

Beregsau, Wojtek, Gross Semlak, Klein

Semlak, Johannisfeld and Folea. There

were also a few people from other

villages.

Until the houses were

built, the people lived in so-called

bunkers. This was a hollow measuring 3

x 4 metres and one metre deep. On top

was a roof, sloping on both sidea, and

which was thatched with reeds. At the

rear was a wall plastered with mud.

There was a small window and a door at

the front. The ground sloped at the exit

from the bunker. When people later moved

into their houses, these bunkers were

plastered with mud on the exterior

walls, too, to enable them to be used as

stables for the livestock in winter. But

now, the houses had to be built. Several

families would usually get together and

build their houses communally. The first

ones to be housed were those with

children. A template was made with

boards, filled with earth and stamped

down. As soon as this was done, the

template was lifted and filled with

earth again. This went on until the

required height was reached. To ensure

everything held together, the walls were

reinforced with twigs. The walls were 40

centimetres (16 inches) thick. There

were two house models – one for small

families, the other for larger ones.

Most people built small houses with one

room and a kitchen. The larger houses

had two rooms and a kitchen. All the

houses looked the same. In front of the

kitchen and the second room was a

covered gangway. Every house received

the same amount of timber for building.

Windows and doors were all the same.

Everyone got these materials from the

building centre via the sector's

building supervisor. The ceiling was

built with bits of wood, or wooden

slats, and mud with straw. The floor was

plain earth. Later, each did what they

could. Bituminous roofing felt was also

used, on top of which carpets could be

laid, if anyone had any. Every house had

the right to a barrel of bitumen (tar,

pitch). These barrels of bitumen were

popular because of the metal containers.

Stoves could be made from them. The

plumber built metal stoves all day and

night long. The ovens were made with

clay tiles. These were thinner than

those in the tiled stoves back home. The

roof of the house was covered with

reeds. It was good, and also durable,

but the reeds were bent, so that in

winter, when the wind blew the snow, the

whole loft would become snow-laden.

Later, people learned from the

indigenous people that the reeds had to

have an underlay of a different type of

reed. This wouldn't be a permanent

solution, but who knew whether they

would be staying here permanently? The

ridge of the roof was knotted with reeds

and the whole thing was tied down with

wire. The walls of the houses were

plastered with mud. Many people didn't

realise they were capable of plastering

walls and corners so smoothly. The

houses were all the same inside and were

whitewashed outside with lime. Once the

houses were finished, the public

buildings were built in the centre of

the village; the village hall, the house

for the police and guard dogs, a school,

a co-operative (the so-called shop), a

cultural building for dances and

entertainment, and a dispensary

(out-patients' department). Finally, in

almost every quarter a sort of alms

house would be built where those who

could not work on the buildings would

have a room. They were mostly old people

who had no family and who were still in

their earthen bunkers. Many of them died

in due course. The public buildings were

all built free of charge (socage work);

only the craftsmen were paid. People

moved in at the end of October, once the

houses had been finished. In December,

all the currency in the country was

changed, but people could only change a

certain small amount. Now, everyone was

as poor as each other. The identity

passes were stamped with 'D.O.' above

the photograph – this meant 'Domicil

Obligator', which basically meant

compulsory residence or house arrest.

People were only allowed to travel up to

12 kilometres (8 miles) from this new

village. If anyone was caught outside

the limit, they were punished harshly.

In the neighbouring town of Hirsova on

the other side of the Danube, twelve

people were caught in the small market

town, the only place one could shop. One

was sentenced to six months in prison

because he wanted to buy medication in

the apothecary for his sick mother. All

the others were sentenced to two years.

They couldn't even have visitors, as

no-one knew where they were. When they

were freed two years later, people heard

that they had to go and work as

prisoners on the Black Sea – Danube

canal, which was built only by political

prisoners.

Five hundred hectares

of cotton were grown by day labourers

from the village. Contact between the

Banaters from the new village was

pleasant. The wages were low, but the

work load (the work stipulated for 8

hours) wasn't too high. The wage was

increased only when double the amount of

work was achieved. 400 hectares were

situated near the State buildings, and

100 hectares on the Danube island

opposite. A small rowing boat took the

workers across when there were only a

few of them, but the ferry was used for

larger numbers. The machines, larger

tools and tractors were also taken

across on the ferry, but the ferry did

not operate every day. The old water

transports were already rotten and

decayed. Our people were frightened of

them and would have liked larger

ferries, or a large boat as well, which

would have been storm-proof. The boats

were rowed by a boatman. Up to seven

people could be accommodated in calm

weather; fewer when it was windy, or

else it wouldn't operate at all. The

Danube was already very wide at this

point. On the island, which was called 'Virsatura'

(Rubble Island), there was a 70-hectare

market garden for vegetables. 30

hectares were for the State farm canteen

and 40 hectares were used for trade.

The smaller part for the canteen was a

garden nursery which used the Bulgarian

patch or bed system. The other part was

worked according to the Banat

Triebswetter system, where the plants

grew in rows and were watered

differently.

Growing cotton was

easy work and also the most lucrative.

At peak times up to 500 day labourers

would be working. This was at tilling

and harvest times. People worked in

groups, and when there was a lot of

work, larger groups were formed. Those

from the old villages grouped into their

own separate villages. Drinking water

was placed at the side of the State

property. A private driver, with his own

horse, was employed for this. He brought

the water from the Danube, which was up

to 10 kilometres (6 miles) away, mostly

using his own barrels. Seldom would he

use the State's barrels. The canteen

kitchen also had a driver to constantly

fetch water and for other purposes. The

Danube was the only source of water. All

the drinking water came from it.

The new agricultural

year began with the deep tilling.

Already early on in the year people

would till the soil, even if it only

looked like strips of bacon. In

Lenauheim this would have been a 'Schollenacker'

(clumpy soil) which they wouldn't have

been able to get any finer. But not

here! After two weeks of sunshine,

everything disintegrated into dust. This

was a sign that the soil was rich in

lime. That which was an advantage here

was a disadvantage for house building.

The only stamped earth houses were eight

in one row. All the others

disintegrated, just like the tilled

strips of land. Only the settlers from

Triebswetter, who were on the bank of

the Ialomita, could make clay bricks to

build with. The old bed of the Ialomita

was south of the Triebswetter sector,

where it flowed into the Danube. The new

village was also situated in this

corner. The water from the Ialomita (Jalomiza)

was bad and undrinkable. The remaining

houses were built with posts which were

set in the ground. Strips of wood were

nailed to these posts, and then packed

with straw and clay. Twenty-four

3-metre-long stakes were used for one

house.

The planting of

cotton was discontinued after two years.

The general cultivation of plants was

similar to any agricultural concern,

with all kinds of plants. A lot of

lucerne and other forage plants were

cultivated for sheep-rearing, which was

a pillar of this economy. There were

10,000 (ten thousand) sheep which were

kept in seven large sheep stalls during

winter. These stalls also served as

protection in lambing time. Immediately

next to them, 200 hectares of rye were

planted for the meadow. This would be

grazed down within two weeks. Apart from

rearing sheep, the second most important

crop was rice. 1,200 hectares of rice

were planted, of which a small part

became overgrown with water grass. These

were planted anew and were regenerated

using crop rotation, such as cereals and

potatoes. The paddy fields were all

watered via a large canal system with

water from the Danube. Large pumps were

used for this. The crop rotation system

was ordered by the Department for the

General Cultivation of Plants.

The threshing of the

grain was done just as it was in the

Banat. Here, there were only threshing

machines which were driven by tractors.

There were no sheaf-binders or

haystacks. Everything was brought by the

oxen and threshed straight away. In some

places, no sheaves were bound at all,

but just forked loose onto the long

harvest cart. This was slow and arduous

work. The conveyor belt which put the

straw straight onto the haystack was not

known in the Baragan. A pile of straw

would be pulled to the spot where the

stack was to be built, by a thick wire

cable about 500 or 600 metres long, with

a loop. At the other end were two oxen

which would pull the wire cable back to

the threshing machine. Again, four oxen

would pull the straw up the stack, which

would be up to 10 metres (33 feet) high.

No rainwater could get into these stacks

as the straw in the centre would already

be compressed by the wire rope being

pulled across it. They were enormously

long stacks which would never have

fitted into the Banat farmyards as there

wouldn't have been enough space. At hay

threshing time, a small tractor was used

to pull the hay up, and the wire rope

was taken back by a horse. This worked

very easily as the wire cable was

already polished smooth. There was a

difference between the conveyor belt

method and this working method; the

conveyor belt method made haystacks the

same height at both ends, but the

haystacks in the Baragan were

wedge-shaped and twice as high. Six oxen

and two more men were needed.

When the deportees

returned home in 1956, the new village

was levelled with bulldozers and new

paddy fields were planted. In the third

tributary of the old Danube (or

Dunerea-turceasca, i.e. Turkish Danube)

there was still a section with about

1,000 hectares of arable land, plus

meadowland for sheep, young cattle, pigs

and bees. Naturally, there was a canteen

and accommodation here, too, for the

employees. Next to this section was also

a detention centre from which the State

farm employed prisoners for the large

jobs. The centre itself also had an

agricultural concern. The prisoners who

were due for release were allowed to

move around freely as drivers. To reach

this section of the 'Strimba' (which was

the name of the island) people used a

sloop, or the ferry which was always

loaded with goods. The sloops were small

motor boats, either with or without a

cabin. The ferries could carry 40 to 60

tons. All the ferries were pulled. There

was also a passenger steamboat which

travelled regularly from Cerna Voda to

Braila. The navigable main tributary was

where the deportees lived.

Wood for burning was

a necessity for the people. The lumps of

roots were bought by the cart load. This

was the best material for heating. It

gave heat twice over; first when

splitting the wood and secondly when it

was burned in the stove. 'Catina'

(tamarisk), which grew along the shores

of the Danube, could be burned green. It

was also the only wood which didn't

float in water.

One special event

during the exile in the Baragan Steppes

was the Kirchweihfest. 'Kirchweih' was

celebrated as though everyone knew it

would be the last one here. The girls

decorated the boys' hats and there were

bunches of rosemary, just like in the

Banat. A 'Kirchweihbaum' (Maypole) was

set up and the personalities were

invited to the sound of brass band

music. There was a big market on the

Sunday to which everyone from the

neighbouring villages came to shop. They

had never seen anything like it. The

Kirchweih girls and boys were all

dressed in their traditional costumes.

The people were amazed as they walked in

time to the music and they asked how

long these youngsters had been

rehearsing walking in time to the beat.

The first autumn was

lovely. This helped people a lot when

building their houses. If it had been

raining, as it usually did in the

autumn, no-one knows how they would have

been able to finish. The winter

following the building work was so mild

that people sat out in the streets, as

they had previously done in the Banat,

at Christmas. Not until the third year

(1953/54) did the real winter arrive. A

snowstorm, the likes of which our people

had never seen before, blew. The

indigenous people called it 'Grivetz' (a

strong, cold north-easterly wind).The

snowstorm held out for three days and

nights. There were snowdrifts as high as

the roof ridges. The snow was frozen so

hard that one could walk on it. In the

morning, the people couldn't get out of

their houses, especially those whose

doors opened outwards. With a door that

opened inwards, the snow had to be

shovelled into the room so one could

creep out, and then clear away the snow

outside. With so much snow there was

trouble everywhere. The lofts were full

of snow, too. And now the Danube froze

over as well. The whole winter long,

there was no river traffic on the

Danube. People reached the island by

foot. A large sledge, which was pulled

across by a long rope from a caterpillar

tractor, was built to bring the tractors

across the Danube for repair. This was a

preventative measure in case the ice

broke, to stop anyone being injured.

According to past experience, the

breaking-up of ice leads to floods.

That's why the State buildings were

evacuated. The rice harvest was still in

the store. The rice was taken to

Tanderei (Zenderei) in large silos. The

military broke through the 4 to 5 metre

high snowdrifts along the road to enable

it to be used for transport. In Tanderei

all the houses were under snow. One day,

a miracle happened. There was a noise

like cracks of thunder in a heavy storm.

Nature's great drama began. On the

Danube, the ice cracked open from the

enormous pressure of water, and blocks

of ice formed 10 to 20 metres high,

pushing into each other and causing the

ice and water to (?lock together?). You

could say it was lucky, as it finally

went down without resistance. The whole

day long, there were people on the

Danube dam watching the rare natural

event.

Something else

happened during this hard winter. 600

sheep froze to death in the snow storm.

These were laid in a pile just as they

were, and used according to need. A good

harvest of leeks enriched the menu.

Cooking was done in these canteens as in

all Romanian military kitchens; stew,

made with water from the Danube. On the

island where the nursery gardens were

the meals were more varied. There were

vegetables around in the garden. The tea

in the morning was made in the same pot

as the mutton had been cooked in

earlier. It always had globules of fat

in it.

It was terrible

during wet weather. Not a single street

was surfaced. There were no stones

around anywhere. It was impossible to

get about without wellingtons, as the

mud and clay was ankle-deep. During the

thaw, you couldn't get around at all

without a stick. After 10 metres, you

had to wipe off the mud from your boots

with the stick. At a funeral of one of

the Lenauheimer women, Father Farkas

from Otelek got stuck in his boots. His

torn socks weren't visible for long. He

stood in the mud. A funeral

service with a comical twist.

Another funny event

took place at work: A group of

labourers, who were busy filling a cold

store right on the Danube dam, saw the

strict Director of the province

approaching. Grischa, a joker from

Bessarabia, made some suspicious

movements which even a blind man would

have seen. The Director noticed it, too,

and grew suspicious of a bulging

rucksack which he was not meant to have

seen. He pointed to the rucksack and

demanded to know who owned it. Nobody

answered. When he asked more

threateningly, Grischa admitted it was

his. The 'almighty one' demanded the

rucksack be opened. Grischa refused. The

Director didn't want a discussion in

front of the other workers and so

ordered him to bring the rucksack to the

office. Grischa immediately complied and

the two of them went. He was to open the

rucksack in front of all the clerks and

employees who had been called in to

witness this assumed theft. Grischa

didn't want to. Then an employee was

ordered to open the rucksack. Everyone

saw that it contained ice from the

Danube. The Director asked why he had

filled the rucksack with ice. He

received the following answer: He had a

needy family back home and was used to

bringing something back home to use from

his place of work. Today it was ice.

Dialects from eight

Banat villages had come together in this

new village. After five years, it could

already be seen that, through everyone

living together and marrying each other,

a uniform dialect had emerged. The basis

was taken from the villages of Lenauheim

and Johannisfeld. Triebswetter had

renounced its french-influenced dialect.

They were already trying to eliminate

their french words. This is how it must

have been for our ancestors, too, when

they colonised the Banat, as the

Rhineland and Saarland dialects were

given up.

In 1955, Romania

wanted to become a member of the UN

(United Nations), but they did not meet

the conditions, as the Human Rights

requirements could not be fulfilled. So

the Communist regime had to rethink

their ways and, amongst other things,

had to release the deportees in the

Baragan Steppes. In the summer of 1955,

the Bessarabians and the Bukowinaers

were set free. This happened quite

suddenly, out of the blue as one could

say. These were refugees from their

homelands of Bessarabia and Bukowina

which Russia had acquired after the war.

Nobody knew what the reason was. They

were deported as Nationalists, without

taking into account whether they were

small or large farmers. It carried on

for several months. Someone on the

Danube ferry heard from an employee of

the Yugoslavian legation that all

deportees who came from the zone along

the Yugoslavian border were to be set

free. The man was right. Shortly

afterwards, the Serbs were released.

This went on until after Christmas, and

then everyone else was released. The

whole day long, new passes were handed

out indiscriminately. It was the middle

of winter, which is why many people

wanted to avoid the journey in cold

wagons. Many were caught out by the

frosty days and suffered. Others didn't

have the necessary money for the journey

and had to sell some of their

belongings. Everyone had to pay their

own travelling expenses this time. On

the journey there, everyone had had a

free pass. Enough wagons for 10,000

people couldn't be supplied immediately.

Many travelled with only a suitcase.

Using carters or

other means, everyone now made their way

to Gura Ialomitei railway station 12

kilometres (8 miles) away with all their

luggage and furniture. It was a new

terminal as the railway hadn't been

continued any further. The large waiting

room was full of returning Banaters. The

luggage was piled up on the ramp

outside. People had to wait several days

for the wagons. As soon as they arrived,

they began loading their stuff. There

was no large livestock any more, but

there was grain. Reasonably priced food

was bought to fill the empty sacks

available. Nothing was sold by weight

using scales here. Everything was

measured with the 'Dubla'. This was a

dry measure of capacity, like the 'Doppelviertel'

used earlier in the Banat. Everything

was loaded up, and off they went. Many

wagons with returnees from other new

villages were added. The wagons

travelled coupled as far as Temeswar.

The weather was beautiful as far as

Temeswar, and then it grew colder and

fresh snow began to fall. The deportees

from Lenauheim arrived home during the

nights between January and March 1956.

The houses themselves needed a lot of

work. They had been neglected and

ruined. These people had built large

straw stoves in the rooms. All the

chimneys needed repairing. And so the

odyssey of the deportation was now at an

end and a new phase of life began.

From Lenauheim 40

families were deported to Dilga, and 44

families in the first transport and 61

families in the second transport, to

Giurgeni. 24 marriages were conducted in

the Baragan between Lenauheimers, partly

with partners from other villages.

Similarly, 23 children were born during

the deportation. Three children and 36

adults died in the deportation

villages.

* * * * * * * * * * *

* * *

|

|

|

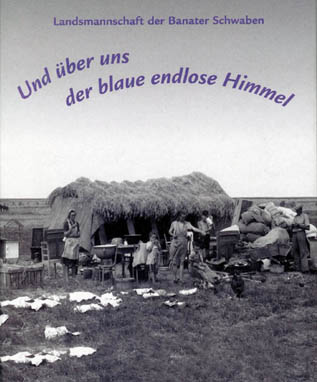

Deportation to the Baragan - Baragan-Steppe Map, Under

the Baragan-Steppe Sky Photos, The

New Villages of the Baragan-Steppe, New Villages on a Map &

District Statistics of the Old Villages

of the deportation

into the Baragan-Steppe (places to areas, districts & counties),

Affected Villages & No. of

Germans Deported & No. of Deaths (Baragan-Steppe 1951-1956) |