|

ZAREV BROD (Endsche)

A German Minority Community in Bulgaria

By Eisenbrunner

Translated By Rose Vetter,

DVHH Editorial, Feb 2, 2013

Original article in German from the 1976 Donau-Schwaben Kalender, Published by

Donauschwäbischer Heimatverlag (Donauschwaben Homeland Publisher) Aalen/Württemberg.

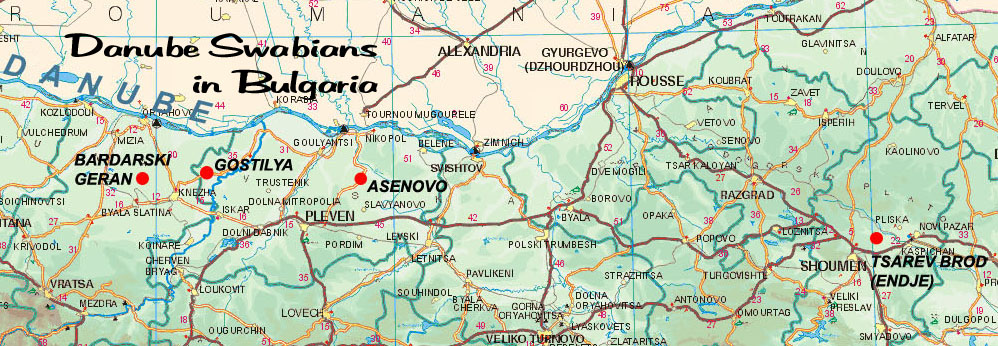

The few German settlements lay isolated in Slavic-Turkish territory, widely scattered, without an administrative and economic interrelationship. On the ethnic map of the 1930’s, these settlements seem like islands in the ocean. Being left to fend for themselves, their ethnic situation was anything but promising for the future, complicated further by the not too friendly attitude of the people around them. This has been manifested by the torturous tale of this colony during the scarcely six to seven decades of its existence.

Zarev Brod (Tsar’s Ford) is situated in eastern Bulgaria, about 11 km northeast of the old fort Schumen (Kolarovgrad). The gently rolling hills and the fertile soil of the region are ideal for grain farming, as well as grape- and fruit growing. Vast wheat-, corn- and sunflower fields, as well as vineyards and fruit orchards, provide the residents with a sufficient basis for their economic progress. Until 1934, the village was still called by the Turkish name, Endsche, indicating the almost five-centuries-long rule of the Ottoman Empire. The area abounds in ruins of former royal castles, indicating a grand Bulgarian past.

With the onset of the Bulgarian national movement in the 18th century, the first step of achieving national independence was to establish a principality, although it still remained under Turkish rule in 1878. At the same time, however, this also set in motion a reverse immigration of Bulgarians living in Wallachia. Succeeding Prince Alexander von Battenberg, Prince Ferdinand von Coburg-Gotha became regent in 1887 and finally attained full sovereignty of his kingdom in 1908.

It was Prince Ferdinand who had solicited colonists in the German settlement regions of south-eastern Europe and Russia. And indeed, many German families followed the call of the German prince on the Bulgarian throne and journeyed hundreds of kilometres into an uncertain future.

The entire settlement process lasted over a decade. By 1899, 117 families had already settled in Zarev Brod. From the South Russian counties, Cherson and Nikolajev, and the Bessarabian county, Akkerman, came the following families: Hummel, Rühl, Müller, Schneff, Braun, Bernhardt, Ihly, Schnitzler, Ruscheinsky, Vogel, etc. The places of birth of these settlers, such as Neukarlsruhe, Altkarlsruhe, Halbstadt, Rastatt, Sulz, Worms, Speyer, Landau, Katharinenthal, Emmental, Landshut, etc. indicate that the descendants coming from these German colonies on the Black Sea, founded by Empress Katharina II, were mainly of Swabian, Allemannic and Palatinate origin. They shared common roots with the immigrants coming mostly from the Banat, such as Hiller, Hayer, Engler, Gruber, Kiefel, Knipfel, Ecker, Zeidler, Langenfelder, Rosenzweig, Warre and others, whose ancestors had also migrated from the south-western German regions in the 18th century. Thus, because of the common dialects, customs and traditions, these settlers lived together in peaceful harmony.

As already mentioned, the settlement process stretched out over a considerable number of years. Not all of the prospective settlers had the necessary start-up capital, therefore, some settled on so-called “Chifliks”(1) and worked the land as half-share farmers (Halbscheidbauern). Eventually they also moved into the newly established German settlements.

Due to the mass exodus of the Turks from Endsche and the surrounding region, large tracts of fallow land became available at low prices. Besides agriculture, the newcomers also tried their hand at introducing grape growing, particularly as the soil and climate provided excellent conditions for viticulture.

Despite their diligence and tenacity, there were setbacks in the young colony. Summer droughts brought about crop failures, which caused many a settler to reach for his walking staff. Ten families returned to Hungary, seven to Bessarabia; another five families emigrated to America.

The much-needed benefit of spiritual and moral support came to the settlers from Father Franz Krings, a young German priest from Kempen on the Rhine. At the age of 25 years, he had been commissioned by his bishop to embrace these German Catholic settlers in eastern Bulgaria; this was in 1898, during the crucial years of establishing the colony.

Initially, Father Franz resided in Schumen (called Schumla by the Germans). Every Sunday a farmer would fetch him to Endsche, where he celebrated German Mass in a villager’s house. After the service he would talk to the settlers about their problems, of which there were many.

After the first small church had been built in 1902, for which the farmers made their own clay bricks, Father Franz moved to Endsche. Soon the settlers built him a clay hut to serve as a temporary home.

After less than a decade, the settlers were able to replace their makeshift little church with a lovely church built with solid materials. Everyone was filled with joy when this church was dedicated on April 19, 1910. But that was not all. Three years later a convent was built to accommodate Catholic teaching nuns from Tutzing, Bavaria, who were to educate the children in their mother tongue. The sisters arrived at the beginning of January 1914, and on January 19, school began for 37 children. This was an important milestone in the history of the village.

The unfortunate outcome of World War I resulted in serious repercussions for the German settlers. Following the advice of the German Consul, those who were not Bulgarian citizens left the country. Among them were Father Franz, the Sisters and about 60 settlers, most of them former Banaters. Only gradually were they allowed to return to their beloved Endsche, finally joined by Father Franz and the seven Sisters from Tutzing. It was a day of great rejoicing when the “spiritual leadership” returned to Endsche on May 13, 1920.

The building of the colony resumed, despite some inclement weather, but also in the face of chicanery by public officials and the envious looks from non-German villagers. For in the meantime, many a German settler had managed to build up a handsome farm with considerable livestock. Some farmers owned as much as 800 decars(2) of land.

In 1938, shortly before the beginning World War II, Zarev Brod had a population of 1851, made up of 334 Germans (18%), 729 Bulgarians, 537 Tatars, 214 Turks and 27 others (Albanians, Romanians, Russians and Czechs).

What are the present-day conditions in the former German settlement of Zarev Brod? These settlers were struck by the same fate of expulsion that befell the other German settlements of Bulgaria. About a hundred residents found accommodation in Bruchsal and surrounding areas in the present-day Federal Republic of Germany; others ended up in eastern Germany or Austria. Today, the displaced “Swabians” of Zarev Brod are scattered in all parts of the world without spiritual bonding to their old homeland. For them and the annals of history, the chapter of “German colonization in Bulgaria” may be considered closed, albeit with a negative ending.

Chiflik = large agricultural estate

10 decars =1 hectare

|

|

Catholic Church, 2003

Altar with ceiling fresco on wood, 2003

Convent garden in Tsarev Brod, 2003

On the way from the cemetery to the convent, 2003

German part of the cemetery outside of Tsarev Brod, 2003

Descendants of the Märzluft-Göbel clan with the Benediktine Sisters

in the Sacred Heart Convent in Tsarev Brod, 2003

Grave of Jakob Göbel from Fegyvernek, Hungary (Maria's great grandfather)

|